Murphy Writing of Stockton University brought another writer for the Stephen Dunn Reading Series on February 11. Author Dionne Ford read from her memoir “Go Back and Get It” which was a Huston Wright Foundation Legacy Award finalist in 2024.

She is a highly-acclaimed writer, professor, and journalist and has published her work in many notable literary magazines and newspapers such as the New York Times and the Virginia Quarterly Review.

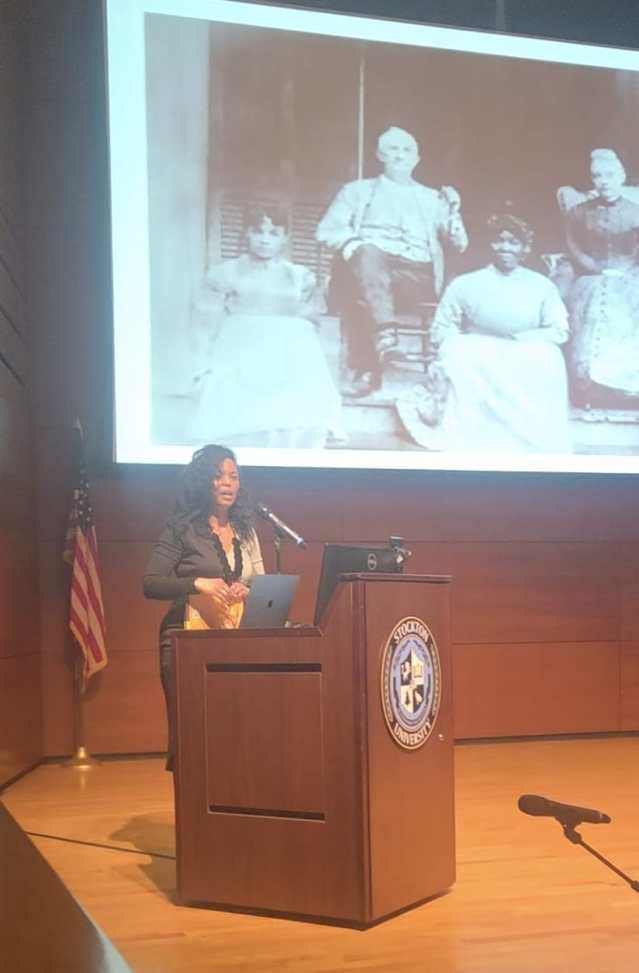

Ford appeared at Stockton to read from her memoir, which stemmed from an old family photograph of her great-great-grandmother. She delved into the difficult and tragic topics of slavery, intergenerational trauma, and sexual abuse from relatives.

She explored her ancestors’ stories as well as her own experiences, detailing the impact of that trauma and what she has done to heal from it.

The prologue of the memoir began with how most African-Americans have white men– likely slave-owners– in their ancestry, averaging at about 19% of one’s ancestry. “If you are going to look for your enslaved ancestors, you will have to reconsider the word, ‘lucky’,” Ford read.

She then told the story of her ancestor, Temple ‘Tempy’ Burton, who was given to Colonel W.R. Stewart and Elizabeth MacCauley as a wedding gift. Elizabeth was unable to have children, but Tempy gave birth to six children fathered by the Colonel.

On her 38th birthday, Ford found the family’s picture on the Internet, which was displayed behind her as she described it of her ancestor, Tempy. She then explained the meaning of the book’s title, “Go Back and Get It”, which connected to the journey she made in uncovering her family’s history and the details of her ancestors’ stories in order to make the memoir possible.

Ford stated, “There’s a name for this kind of pilgrimage. The Akan of Western Africa call it ‘Sankofa’. […] Sankofa means to ‘go back and get it’, or, ‘it is not wrong to go back for that which you have forgotten’.” The family photo she displayed was used for the ‘family tree’ drawn on the book’s cover.

She described the difficulty she had in tracking down her family tree and ancestral information, but also noted her technological advantage. “Technology sort of caught up to my aspirations,” she stated. “When you are willing to find information on enslaved people in this country, it’s very difficult because enslaved people were treated like property. Oftentimes, there aren’t names attached to their records, sometimes not even identifying information. It was really, really difficult to go through documents looking for someone without a last name, maybe having some idea where they might’ve been born. The fact that I was able to find this picture on the Internet is this big, huge, lucky chance.”

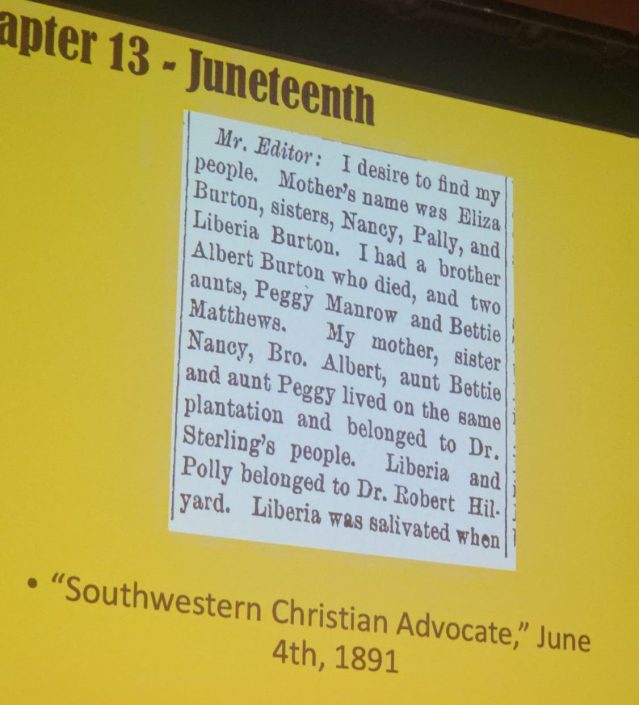

One of the chapters, titled “Juneteenth”, detailed a newspaper clipping from the Southwestern Christian Advocate, from the June 4 1891 issue, where Tempy had written a letter to the editor to find her relatives that were separated from her through slavery. “Being able to find something that my great-great-grandmother printed in the newspaper was really amazing. First of all, [being] one generation away from slavery: she was literate.”

Ford noted how enslaved people were never permitted and oftentimes severely punished if they attempted to learn reading or writing. Tempy, however, both read and wrote, enabling her to put in her request to the newspaper. She was an inspiration to Dionne Ford, who has studied to be a journalist.

She read out the full ad, then described: “Tempy asked that any response be sent to her, care of W.R. Stewart, Esquire– my great-great-grandfather. Most ads requested that letters be sent to the searcher’s church or minister, so why did she want Stewart, who was bound up in this fissure in her family, to be involved in the mend? Perhaps Stewart had been one of those not-entirely-inhumane slave-holders that Harriet Jacobs likened to ‘angels’ visits’, few and far between.”

After the reading, audience members were free to ask Dionne Ford questions about the reading and her story. A professor asked, “I’m curious about Tempy’s ongoing relationship to those who enslaved her and what you were able to uncover of that story,” noting that Tempy remained with the Stewart family in the 1890s (the time the photo was taken), long after slavery had been abolished.

Ford answered, “It looks like a family photo, which is why it was so interesting to me; why would my great-great-grandmother take a picture with the people that enslaved her? The conclusion I’ve come to is the two girls sitting on each side: however they were formed, this was a family; they were children. From what I’ve learned of [Tempy], a very religious person, a woman who was held in esteem in the 1800s […] when she died, had several Black and White ministers come and speak at her funeral, and a woman who owned property at the end of the 1800’s; a Black woman in Mississippi who owned her own home. […] Her staying in this family had to do with her children and their welfare.”

Once dismissed, free copies of the memoir were offered to the attendees, and Dionne Ford signed them outside of the Campus Center Theatre. Everyone left with deep admiration and respect upon hearing her story and her ancestors’ stories.

Ford’s memoir can be purchased here. To see Murphy Writing’s information about Writing Workshops and Retreats, visit this site. The next event will be part of the World Above series at the Noyes Arts Garage, bringing Lennox Warner to the stage.

Categories: Campus Life