The holiday season is widely known as “the most wonderful time of year.” It is also one of the most stressful times of year according to many people. From gift giving with friends and loved ones, to bright and whimsical decorations, to the hopes for snow outside, the images know as Christmas have etched themselves into modern society. How did this iconic holiday gain its reputation? Where did all these customs and traditions come from? From its ancient roots, to exchanges with other cultures and religions–even once being banned–Christmas has truly seen it all.

As I had mentioned in one of my earlier writings on the Mari Lwyd, many cultures that experienced winters held special festivities, especially during the middle of the season. In particular, the winter solstice was especially prominent, marking the end of days growing shorter and the first hints of spring. One such example was seen by the Norse in Scandinavia in a festival called Yule. Large logs would be brought in and set ablaze, for which a feast took place the entire time it took the logs to burn up (up to twelve days in some cases). Each spark from the flames hinted at the birth of a calf or a pig the following spring.

Pagans in Germany paid tribute to their mid-winter god, Oden. It was believed that Oden would eliminate those he witnessed out of their homes on mid-winter nights, so most chose to stay inside. For Romans, winter brought the festivities of Saturnalia, which honored the god of agriculture, Saturn. Held from the week before the solstice to the month after, it was a major time of celebration. Food was plentiful for all, and even slaves and peasants got to join in on the fun. Some were even granted higher social standing during the time. This time also brought on Juvenalia, a tribute to Roman children as well as a celebration of the birth of the god Mithra. Mithra’s birthday was considered the most sacred day of the year.

Mid-winter had another thing going for it in terms of all these feasts: beer and wine typically finished their fermentation process by this point, as well as having the preserves from the harvest season earlier in the year. Many livestock animals (that were not intended for breeding) were slaughtered so they did not have to be fed during the winter. This in turn would provide the only substantial supply of fresh meat for most people during the year.

Now we get to post-Christianity Christmas. Before its adoption by Christians, Easter that acted as the biggest holiday of the year for Christianity. Christmas marks the birth of Christ, but prior to the fourth century, it had no official date. While there has been evidence suggesting his birth around spring, Pope Julius the First went with December 25th as the date, hoping to absorb it into the Saturnalia festival. By the sixth century, December 25th was recognized as the birth of Jesus Christ of Nazareth. By the eighth century, Christmas celebration was very widespread in Europe.

The Middle Ages saw a different means of celebrating Christmas as we know it today. It was a very bright, bold and raucous holiday, not too dissimilar from Mardi Gras in contemporary times. The poor were treated to the highest quality food and drinks, while the wealthy threw elaborate festivities to entertain them. Then things got serious.

By the early part of the 17th century, massive religious reforms rippled across Europe. Backed by Puritan forces, in 1645 Oliver Cromwell overthrew British Parliament and banned Christmas as part of his vows. What a guy. The punishment for celebrating: a most diabolical fine of five shillings (many still secretly celebrated anyway). This ban found its way to colonial America, but thanks in part to popular demand in Europe as well as fresh waves of immigrants, Christmas had a comeback.

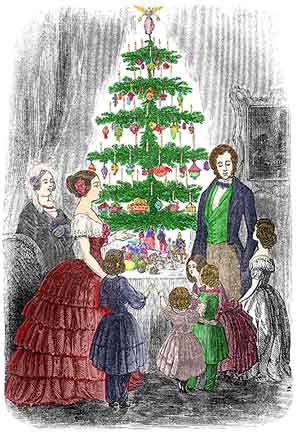

Following the American Revolution, the country did not celebrate it as enthusiastically as today, though it eventually earned its place as a federal holiday by 1870. By this point, Christmas had become much more centered on quality time with family and friends, with emphasis on peace and tranquility. However, modern traditions like Christmas trees were still seen as unusual in the first half of the 1800s. Many thought it was pagan. Paganism refers to any polytheistic religion worshiped after Rome adopted Christianity…and–by 19th century standards–what is more pagan than bringing a live tree into your house?

Paganism was viewed as a force of evil and treated as taboo. By the 1890s, attitudes had changed in America, and more and more households set up Christmas trees every year. Earlier decorations were often homemade. Electricity in homes would set up the foundry for Christmas lights. European countries like Germany strongly influenced contemporary Christmas traditions in America, but preferred smaller trees, usually around four feet tall. Americans had preference for trees that ran from floor to ceiling. Can you name a more American way of doing something?

Today Christmas has bloomed into one of the world’s most celebrated and recognized holidays. From a celebration of the solstice and feasts, to its adoption by Christianity, to the development of traditional aspects of it, this holiday has seen a plethora of celebration styles across multiple cultures and times.

Categories: Campus Life, Entertainment